When discussing youth participation in sports, we hear about age guidelines for dance training, warnings about common gymnastics injuries, and everyone seems to have ideas about coaching team sports, but what about circus? What do we know so far and what can we learn from other sports when it comes to what our youth circus artists should and shouldn’t be doing and/or what to look out for?

First off, where does the information I am about to present come from?

Much of it is pulled from our understanding of how children skeletally mature, what we’ve learned from research on sport training in youth in general, and the specific loads that come with repetitive jumping and tumbling.

It’s also always good to remember that circus science and research is very very new, but youth circus training has a long history in the United States.

The majority of our adult training programs have only been established since 2010, but the tradition and programs around youth circus are much older. These programs include: Sailor Youth Circus (1949), Peru Amateur Circus (1960), Wenatchee Youth Circus (1952), St. Louis Arches (1989), and Circus Juventas (1994).

So, while for the most part we can’t point directly to the “circus research” there is a lot of practical knowledge we have gained and a lot we can learn from the research in the youth sport world. Of course, this also means there is always room to learn more and for our thoughts to change and grow with that new knowledge.

Let’s start with some general important things to know about growing bodies and then go into the most common specific questions I get.

The biggest consideration is that our young artists are STILL GROWING.

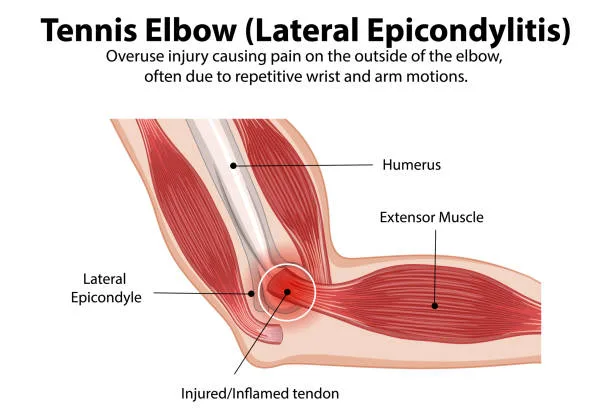

Their bones are softer and more elastic and have “growth plates” that allow the bones to add length. (White) This means that they are more at risk for overuse injuries like stress fractures with their softer bony tissues, and inflammation at the insertion of tendons on the bone, usually from larger muscles like the quads. (Brenner and Watson)

Another concern is that amazing growing brain of theirs! It’s hard to see the injury and it is therefore important to know the signs and to get youth cleared by a medical professional to return to training to ensure that the brain has healed and prevent more lasting damage.

What are overuse injuries?

Overuse injuries generally occur for two reasons.

One, is repeatedly loading tissues in the same way. For example, a pitcher with throwing, or a ballet dancer jumping, or gymnast vaulting onto their hands. Having lots of ways of moving the body helps. Avoiding overuse is one reason why you hear about not having kids specialize in one sport too early. (Brenner and Watson)

The second is lack of adequate rest and recovery. Yes, this means sleep, but it also means giving time and creating an environment for tissue to recover, like the right nutrition to fuel the body to do all it needs to adapt and recover. (I know the next question is “how long does the tissue need?” and the answer is

that it depends on the tissue type and condition and the intensity of the stress that was on it… basically it would be a whole other blog post!)

How can we tell when a youth artist-athlete has an overuse injury?

In general, they will have a gradual onset of pain that becomes worse overtime, is worse with activity, and is tender to the touch and/or swollen. This doesn’t sound great, I know, but the good news is that by checking in with our students/children and listening to their responses over time we can (hopefully) catch these injuries early when they are easy to treat by modifying their activities.

Onto the specific youth-centric caring and brilliant questions that I get most often!

“I’ve heard youth athletes shouldn’t strength train. Is it safe for students to do conditioning?”

The short answer is Yes!

Strength training used to be considered questionable for youth, but as researchers gathered data they did not see an increased risk for youth injuries. Strength training is now considered beneficial for youth athletes when performed with good technique and at appropriate weights for the youth athlete. (Faigenbaum and Myer)

“In ballet there are age restrictions on when a dancer can go on to pointe. Is there an age limit for foot locks?”

The short answer is no, there is no age restriction for foot locks. But more importantly, WHY?!?

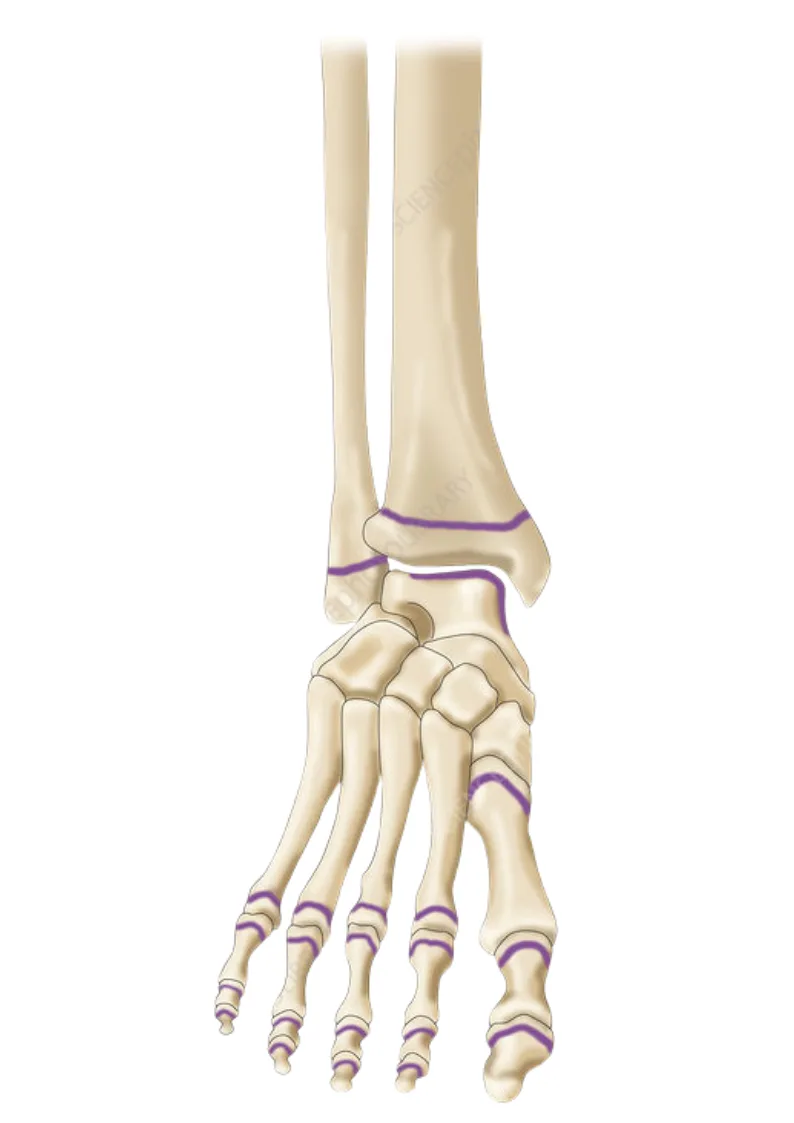

Well, a few reasons. Let’s start with why there is a guideline in ballet. Unlike with youth strength training, we have found a high occurence of stress fractures in ballet dancers, specifically in their feet and especially in young dancers on pointe. (Albisetti et al) This is because they are dancing on their feet for hours at a time, landing repetitive jumps, and when they go “en pointe” the loading in the direction of the bone shaft can increase the stress through the metatarsals (long foot bones) and especially at the growth plates. (Albisetti et al) Waiting until their bones are more solid AND they demonstrate the strength and stability through their trunk, hips, ankles, and feet helps reduce the number of youth fractures.

In aerial, youth approach foot locks a bit differently than a ballet dancer. First off, they are not only doing foot locks vs dancers who are always on their feet. Sometimes our aerialists hang by their hands and sometimes they support themselves from their hips or knees. Second, when they do foot locks they are usually not loading them dynamically or along the length of the bone. They are more likely wrapping the foot side to side causing a compression force and then using it to support the body in a relatively static position. Taken all together these factors are much less likely to cause overuse injuries.

The most important factor when considering foot locks in youth is whether these injuries have been seen in an young aerial artist population. So far, the answer is no. This is fantastic news. There does not seem to be the same fracture risk as we see in pointe work.

All that being said, if a foot lock (or any skill) is uncomfortable or causing pain, try looking at the student’s wrap and performance and if that doesn’t fix the problem consider if there is another way of wrapping the leg or ankle to still achieve the goal, or bypass the skill for now and come back to it. There is always more to learn.

The last “big question” I get asked is:

“Are neck hangs safe for kids? When is it too early to train them?”

This one is a little tougher as there is limited literature out there about what happens at the neck with a proper neck hang. However, we can start by relying on the information we have gained from years of teaching youth circus by looking into the question of whether we are seeing injuries from neck hangs. The short answer is mostly no, we are not seeing a trend of injuries. The biggest barrier to safely performing a neck hang is strength and that strength comes with age and skill training. What clinicians are seeing is that if issues occur they tend to be similar issues to those that adults have which include numbness or tingling in the arms, often after having issues or pain training a neck hang.

But what does the research say? By 8-10 years old the cervical spine size and shape is that of an adult. (Lustrin et al.) By 12 years old the injury data in general for youth does not differ from adults. (Platzer et al.) So, if we were to go by just the numbers and bony changes, I would be comfortable allowing neck hangs in a strong prepared 10 year old.

For neck hangs at any age the key is a gradual progression to increased weight bearing and monitoring feedback from the artist. Are they having discomfort or pain or numbness or shooting pains, feeling of dizziness or seeing stars/sparkles/blacking out? Discomfort? They’re good to go. The others, back up a step (or two) and move forward cautiously.

It hasn’t been asked as much, but I would give similar advice about youth performing chest stands. Though they may have the flexibility to be there, do they have the strength and how do they feel when they are in the position?

This is a great spot to discuss one of the things that I think is most important in education when working with youth… What is pain? Hurt? And discomfort?

How do we talk about them and distinguish between them?

When you are working with youth it is an opportunity for education around the language of pain. Yes, circus hurts, but what is the difference between the “pain” of pressure from your acro partner’s foot or trapeze bar on your hips vs sharp pain at a joint or burning pain shooting through a nerve pathway. By giving youth more words we can improve their understanding of their bodies and their ability to communicate about what they are feeling. It’s a skill and we can help them learn it!

What am I concerned about in youth circus training?

I am most concerned with the injuries that we do see as quite prevalent in related activities like growth plate injuries at the wrist in gymnasts or “Osgood Schlatter” injuries with inflammation and damage at the insertion of the quad muscles on the shin bone at the tibial tuberosity. (Benjamin et al.) The first is due to the repetitive loading of the radius, a bone of the lower arm, in tumbling. This is not unlike the foot bones in ballet dancers. The second is due to high loads of repetitive jumping, which is present in many sports. Both of these usually begin as irritations or pain with activity. If they are managed with good communication and a reduction in load, they usually resolve without any lingering issues or damage.

The key to preventing an irritation from becoming a more major injury is to have an open dialogue that invites conversation. These youth artist-athletes may not have the words yet for what they are experiencing and if they think that “circus hurts” but don’t know what that means, they are at a disadvantage.

What does this all come down to?!?

Knowledge is power. Humans are adaptable. Kids are resilient. All artists need to be heard and respected and educated on how and when to talk about pain in their bodies.

Bibliography

White, Tim D., Michael T. Black, and Pieter A. Folkens. Human osteology. Academic press, 2011.

Brenner JS, Watson A; COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS. Overuse Injuries, Overtraining, and Burnout in Young Athletes. Pediatrics. 2024 Jan 1;153(2):e2023065129. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-065129. PMID: 38247370.

Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Resistance training among young athletes: safety, efficacy and injury prevention effects. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Jan;44(1):56-63. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068098. Epub 2009 Nov 27. PMID: 19945973; PMCID: PMC3483033.

Albisetti W, Perugia D, De Bartolomeo O, Tagliabue L, Camerucci E, Calori GM. Stress fractures of the base of the metatarsal bones in young trainee ballet dancers. Int Orthop. 2010 Feb;34(1):51-5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0784-3. Epub 2009 May 5. PMID: 19415273; PMCID: PMC2899256.

Lustrin ES, Karakas SP, Ortiz AO, Cinnamon J, Castillo M, Vaheesan K, Brown JH, Diamond AS, Black K, Singh S. Pediatric cervical spine: normal anatomy, variants, and trauma. Radiographics. 2003 May;23(3):539-60.

Platzer P, Jaindl M, Thalhammer G, Dittrich S, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. Cervical spine injuries in pediatric patients. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2007 Feb 1;62(2):389-96.

circus science in your inbox

Not already getting the newsletter?

Join HERE to stay up to date on the latest developments in circus science, circus body education and events with The Circus Doc!